Harriet Feigenbaum, Sculptor: Coal Land to Land Art

Here is my monthly article on art and anthracite. We'll return next weeks to French country living, to neighbors, to victims and to bullies.

The year is 1965. A young woman gets on a bus in New York City and rides it to Wilkes Barre. For her summer vacation, she wants to go somewhere exotic and unknown, but not too expensive or far from home. She chooses the coal region.

Upon arrival, she asks how to get to the nearest coal breaker. She is directed to the Glen Alden Coal Company in Ashley. She meets a company executive and asks permission to make some drawings. He tells her to come back the following day, between shifts. That way she can draw the men. She shows up the next day and the next. On her third trip, she is given coveralls, a hard-hat and a lamp. She goes underground and begins to sketch.

The woman’s name is Harriet Feigenbaum. She was born in Brooklyn in 1939. Her summer trip to the coal region is the first of many across two decades. She is a sculptor but also a fine draftsman. There’s something about the coal region that draws her back again and again.

When she visits the company’s open pit mine, her guide, in a very matter-of-fact way, describes the harmful effects of mining, not only on miners but on the inhabitants of the region. Fatalities, fires, road collapses, sulfur in the air and water.

When she asks what the company can do, her guide replies, they put up a fence around polluted or dangerous zones.

Harriet Feigenbaum did not forget what she saw, neither the beauty nor the devastation. When she returns to the region in 1979, she has not come to sketch but to make of the land the palette, the material and the purpose of her work.

Between 1965 and 1979, much has changed.

On December 24th, 1968, astronaut William Anders, as part of the Apollo 8 mission, takes “the most important photo ever made.” From the spacecraft, he snaps “Earthrise,” the first photo of our planet taken by a human in outer space, a mirror of the Earth as never seen before: breathtakingly beautiful, fragile, and alone.

Inspired by the photo, artists too see the Earth in a new way. It becomes their subject and their material as they create “land art,” sculpting directly into the Earth itself. Drawing attention to geological change, they sound an alarm: our planet is in danger.

One of the most emblematic works of the period is Robert Smithson’s “Spiral Jetty,” an earthwork jutting into the Great Salt Lake in Utah. In 1970, over 4 weeks, the artist created his spiral, 1500 feet long and 15 feet wide, using front loaders, dump trucks, and the materials the environment made available to him. Since that time, the spiral has disappeared and reappeared. Today it is outlined by the lake’s crystalline salt that captures the light of the sun.

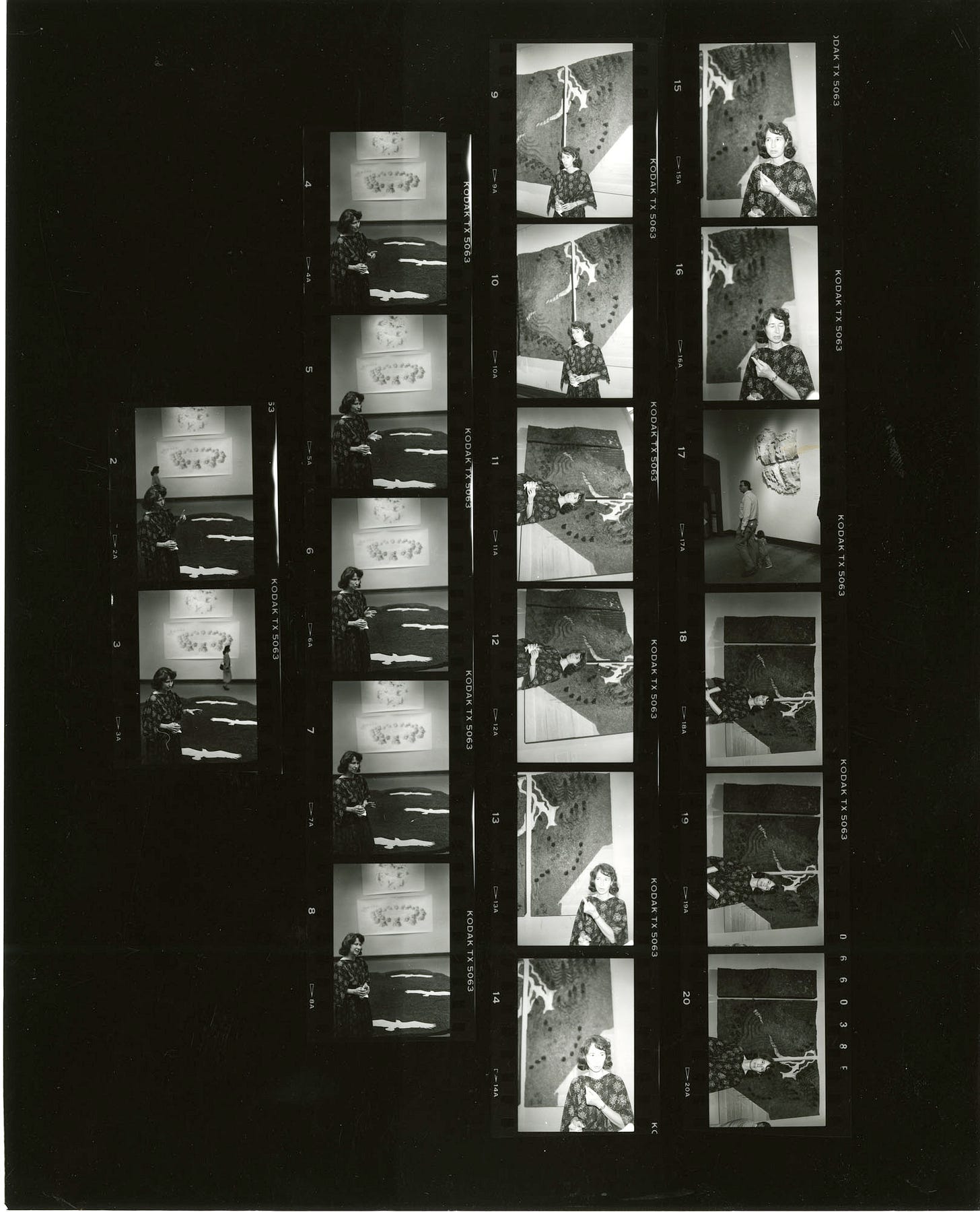

During the same period, Feigenbaum’s sculptural earthworks followed a different path. Like Smithson’s, her work was often monumental, but it was temporary, installations in public spaces that were dismantled at the exhibit’s end. A law effecting the anthracite region, the 1977 Surface Mining and Reclamation Act, changed that.

When she returned to the coal region in 1979, her goal was to combine land art and reclamation to make something permanent.

Before proposing her services, Feigenbaum researched which plants would help stop erosion and reduce the acidity of the soil. Unlike Smithson, who transported vast quantities of earth and dramatically changed the terrain, she hoped to create new landscapes by adapting vegetation to severely damaged sites while respecting the lay of the land.

In the early 1980’s, Feigenbaum went to work on a privately owned portion of Storrs Pit in Dickson City near Scranton. There she created “Willow Rings.” Around a coal sedimentation pond, she planted two rings of willow trees, known to prevent soil erosion while purifying water. On surrounding culm banks she planted diagonal and intersecting rows of pines interspersed with grape vines, both well adapted to acidic soil.

Where there had been coal waste and pollutants, she created the illusion of wetlands surrounded by rolling forested hills. Respecting the contours of the site, she planted and created a space to welcome new life.

In 1986, an exhibit devoted to this work, “Harriet Feigenbaum: Reclamation Art,” was organized at the Pennsylvania Academy for the Fine Arts in Philadelphia.

In the 1990’s, an elevated highway was built over the site, which was officially declared “derelict.”

In 2023, a writer and art critic, Alex A. Jones, set out to search for what remained of “Willow Rings.” She discovered evolutionary art. From the overpass, she saw a decaying landscape. Close up, she discovered a beaver dam, the life that Feigenbaum had hoped to regenerate, and despite the continued presence of pollutants, the emergence, not the illusion, of wetlands.

In “Willow Trees,” art collaborates with nature and becomes process. How much did Feigenbaum’s work contribute to this new ecosystem? We cannot know, but here art is not a piece in a museum. It is as changing as our world.

********************************************************************

To go further: here is a link where you can discover more of Harriet Feigenbaum’s art: Harriet Feigenbaum

Or read this excellent article by Alex A. Jones: On Harriet Feigenbaum

Très intéressant.

C’est étonnant. J’ai vu une émission tv qui c’était intéressé au même sujet.