I love to walk on forest paths. I walk silently atop fallen pine needles bolstered by deep black layers of earth and decay. Above my head, the branches of pine and hemlock heave and swell in the breeze with the same placid rocking as the sea at low tide. Light filters through the trees and falls to the ground, a shower of flickering gold coins that glisten and then flee beyond reach.

Is it a love of nature that brings me here or the loving memory of a book I read as a child?

My Aunt Jean took my sisters and me for long walks when we were very young. She turned us into walkers and we traversed Pottsville from east to west. We also walked in the woods, in a place we called Agricultural Park, a pine forest above the East Side Pool, located at a bend on East Norwegian Street, just before the boundary between Pottsville and Mechanicsville.

The swimming pool was directly linked to the forest. Lacking a filter system, the stone and cement pool was fed by water flowing down a chute from a reservoir in the woods above. In times of drought, the pool had to be closed because the flow of fresh water stopped and green algae formed on the surface. When it did flow, a waterfall to my child’s eye, it kept the water clear and extremely cold.

Outside the pool, sloping down towards the street, there was a playground: swings, see-saws and a merry-go-round, the kind we propelled with our feet, holding to a metal bar, running in circles, hopping on when we’d built up speed.

By the road stood a concession stand with a jukebox and a macadam dance floor. We never went there. It was for the “big kids,” who bought sodas and danced the jitter bug. I remember watching them, hoping to never grow up.

With out aunt, we walked up a gravel road that rose above the playground and the swimming pool. We could not go to the reservoir, protected by a high fence, but we entered the surrounding forest, where we passed from sun into near darkness, sheltered by a canopy of hemlock branches. We were young, we believed in magic, and the golden droplets, stealing through a gap in the branches, falling, disappearing as quickly they touched the black earth, were like fairy dust.

Is that why I so loved Little Red Riding Hood? Did I recognize our sun-dappled path in the forest where Red Riding Hood walked to her grandmother’s house? Or did the illustration awaken in me a desire to search in nature for what I had discovered in art?

I have no answer to those questions, but I can say with certainty that I love today, as much as I did then, the illustrations in the Little Golden Book edition of Little Red Riding Hood.

The drawings are by Elizabeth Orton Jones, an artist and illustrator of the highest caliber. Though her style is not the same, I’d place in a category with Edward Gorey, born in Chicago, like Orton Jones herself. Still today, Gorey has a cult following. Elizabeth Orton Jones does not, but I’m sure many remember her, perhaps not by name, but for her illustrations in books like Little Red Riding Hood or Prayer for a Child, which won her a Caldecott medal in 1945.

Both attracted by French and France (Gorey studied French at Harvard, Orton Jones studied fine arts in France), they died in New England, Gorey at age 75 in Cape Cod in the year 2000, Orton Jones in a red wooden house in Mason, New Hampshire, where she moved in the 1940’s and lived until her death at 95 in 2005.

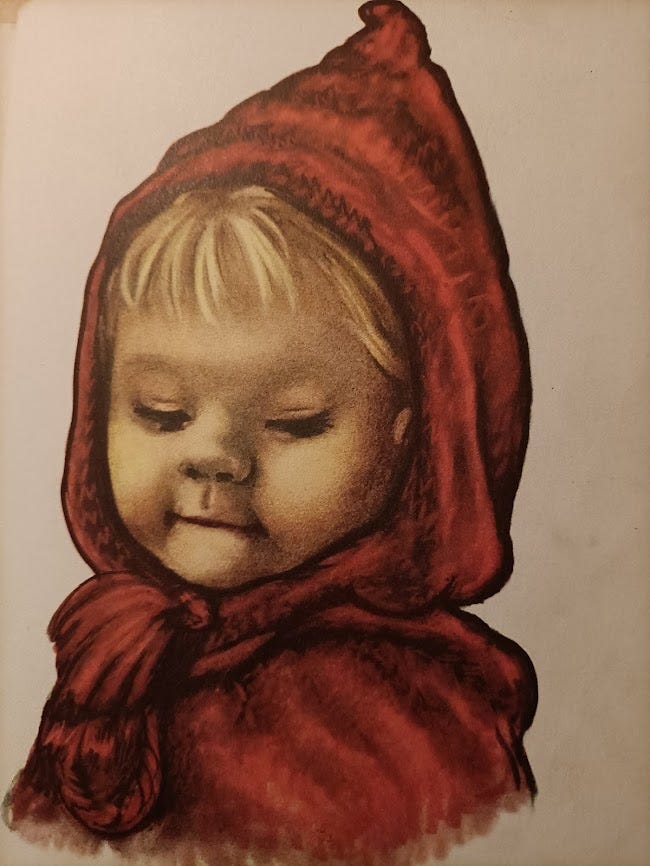

Her Little Red Riding Hood, for many reasons, had a lasting impact on me. Surely I recognized the forest, so similar to pine forests in and around Pottsville. And who would not fall in love with Little Red Riding Hood, so sweet, so kind, so strangely independent for a child her age? Her mother sends her off to her ailing grandmother’s with a pat of butter, cake and a bottle wine. After tying her hood beneath her chin, she heads into the woods alone…

We’ve all heard the story. We know she met the wolf lurking in the forest. We know what happened to her grandmother and to the child herself. We know the passing hunter saved the day.

As a child, did I suspect how out of tune the words are with the drawings? Rereading Elizabeth Orton Jones’s retelling of Little Red Riding Hood, I’m aware of the covert violence, yet the red of the little girl’s cape is the closest we get to blood. The wolf eats the grandmother; then he eats the child. Furtive, bloody work!

The hunter’s work is bloody too—though we don’t see it. With one fell swoop of his ax, he chops off the wolf’s head and out pop Little Red Riding Hood and her grandmother, miraculously intact.

For hundreds of years, Little Red Riding Hood’s tale has been told and retold—and interpreted in ways that would escape a child. Elizabeth Horton’s Jones’s retelling is strangely reassuring—and it’s the strangeness that disturbs me now.

Holding the precious book in my hands, admiring the care brought to creating the illustrations, I realize Little Red Riding Hood lives in a world of women at the mercy of men. Her mother sends her off with a basket for her grandmother. There is no father in the picture and Grandmother lives alone.

The wolf is a predator hungry for blood. The hunter is a predator too as he depends on killing animals for his livelihood. Studying the illustrations of the wolf, studying the hunter, I notice they have the same eyes, the hunter’s, more benevolent yet with the same sinister slant.

Has too much life got in my way, clouding my reading? Once again, I don’t know.

Fairytales are often stories of initiation. There are versions of Little Red Riding Hood where the little girl outsmarts the wolf, others where both she and her grandmother perish, still others where the sweet child is clearly a stand-in for a prostitute. In French, “elle a vu le loup”—she saw the wolf—is a euphemism for a girl’s loss of her virginity. All this escaped me as a child.

In the book’s final scene, so carefully and lovingly rendered, the hunter and the grandmother sit on a high-backed wooden bench at a table where Little Red Riding Hood joins them, seated on a cushion on a straw-bottomed chair, her red cape draped over the back.

As a child, I so wanted to be there too and that table became an aspiration. Covered with a beautiful hand-woven blue-and-white linen tablecloth, the tabletop is what I’d call an “active still-life,” blue and white dishware (just like my dishes today, bought at a flea market in Paris), stout wineglasses with a wide base, surely Bohemian crystal, a hand-blown wine bottle with a nubby surface, filled with red wine.

The cake is there too and the pat of butter and a small milk-glass vase much like one of my mother’s, filled with the flowers Little Red Riding Hood gathered in the woods.

Best of all, the courageous little girl is holding a cordial glass, its bowl no bigger than a thimble. She holds it to her mouth, sipping wine. I knew someday I too would be sipping fine red wine from a crystal glass.

And both Little Red Riding Hood and I know that, be it a forest trail or the path of life, for a girl or a woman, the road to independence is never easy. Wolves lurk in the darkness, needles strew the way.

It is a journey that never ends.