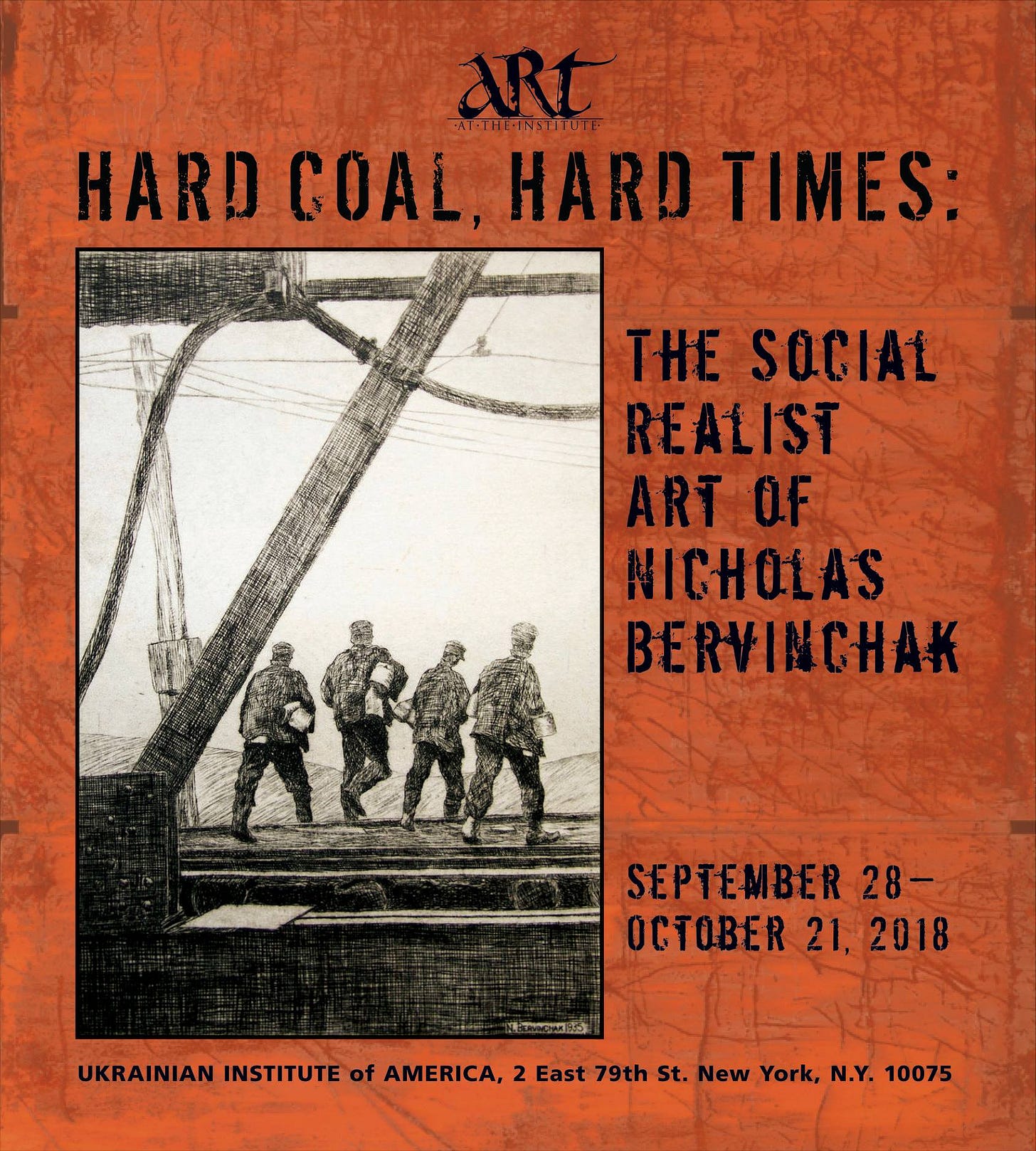

Nicholas Bervinchak: From Breaker Boy to Anthracite “Rembrandt”

Here is my latest "Anthracite Artists," appearing today in newspapers throughout the anthracite region of Pennsylvania. If you enjoy this or any of my articles, please send them on to friends. Thanks!

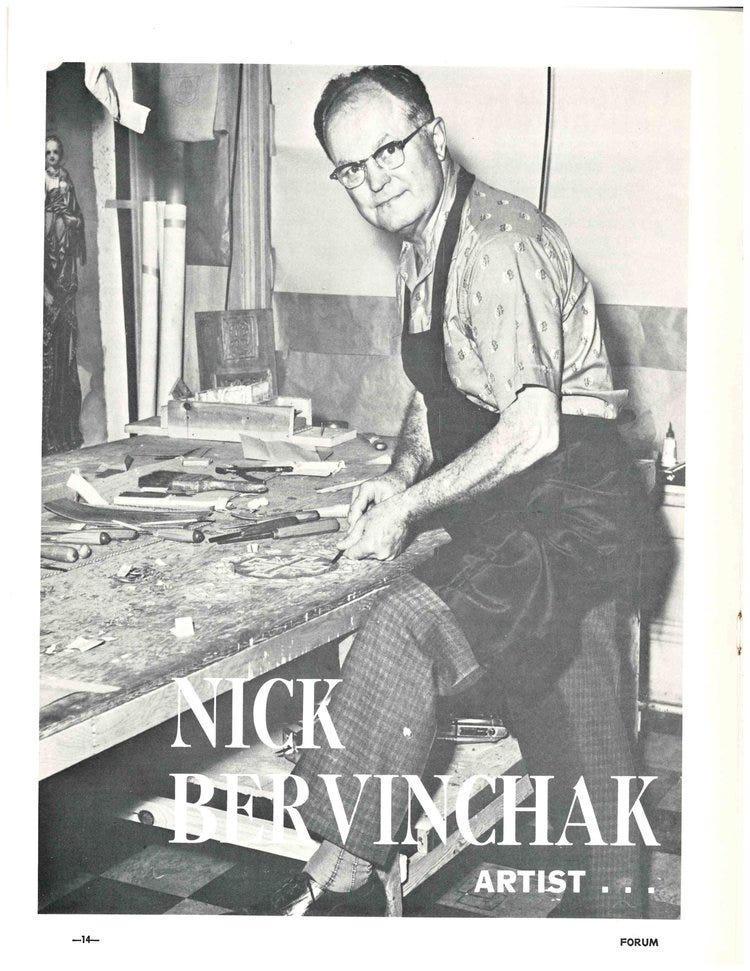

Painter, etcher, woodcarver, and carpenter, Nicholas Bervinchak said of his lifelong journey in the arts, “There are no short cuts to becoming an artist.” And he knew what he was talking about.

Nicholas Bervinchak was born in 1903 somewhere between Shenandoah and Mahanoy City, Pennsylvania. His parents were Lemkos, a minority whose homeland spanned parts of Ukraine, southeast Poland and Slovakia at a time when that corner of the world was part of the Austro-Hungarian empire.

Nick lost his father to a mining accident when he was 5 years old (and if I call Mr. Bervinchak “Nick,” it’s because I met him at his home in Minersville in the early 1970’s. He immediately put me at ease and had the simple elegance of a true gentleman). His mother remarried and her second husband was injured in a mine near the mining patch of Primrose, where the family lived. Nick, the oldest, had to leave school. At age 15, he was working as a breaker boy—and he was drawing.

He made his first drawings on scraps of butcher paper. He tried painting on wood or cardboard, using house paint and cooking oil. He worked nightshift in the mines and sketched and painted by day.

In 1924, he was working as a miner, laying track, timbering galleries, drilling holes for dynamite. When he learned a “real artist” was painting the ceiling and altar of Saints Peter and Paul Byzantine Catholic Church in Minersville, Bervinchak went to see him with a religious painting he had done himself.

That artist, Paul Daubner, born in Hungary and trained in Europe, was so impressed he took Nick on as an apprentice, telling him he’d pay him as much as he earned in the mines. When he saw one of his ink drawings, he encouraged Bervinchak to take up etching, to which the young man responded, “What’s that?”

But Bervinchak learned fast. Daubner explained the method of copperplate engraving. Nick took it all in. He couldn’t afford the equipment, so he improvised. He used a phonograph needle inserted in a pencil holder to engrave his drawings on sheets of discarded copper found in and around the mines.

Without a press, he came up with an ingenious method, using pine pitch, honey and a candle, cardboard and tablespoons. Instead of a printing press, he used muscle grease and the back of a spoon to “press” his drawing from the copper plate to paper.

Daubner couldn’t believe his eyes. He’s as good as Rembrandt, the older artist exclaimed. A few years later, he took some of Nick’s etchings to an art show at Washington Square in New York. They sold like hotcakes and Bervinchak won first prize. With his earnings, he did not buy a press. He built one from scrap iron salvaged around the mines and used it till the end of his life.

In 1925, Bervinchak travelled to Pottsville to show one of his paintings to George Luks, who was exhibiting at the Pottsville library. The New York artist encouraged him to continue, recognizing in Bervinchak’s work the compassionate realism he so admired.

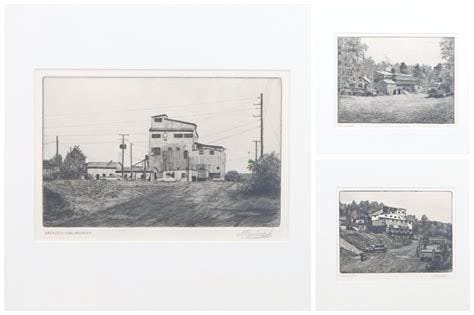

Until his death in 1978, Bervinchak etched over 180 copperplates. During the Great Depression, his etchings documented the truth of the lives of miners and their families in the patches of the anthracite region.

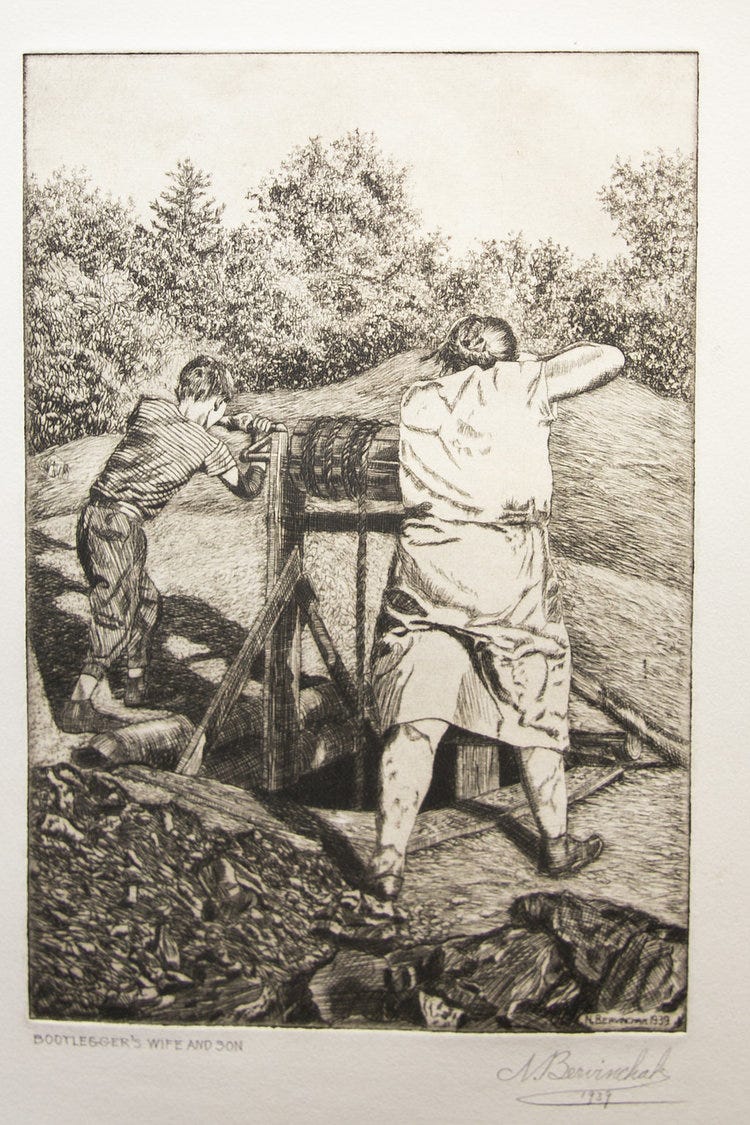

At that time, the big mining operations were laying off workers in droves. In Schuylkill County, many miners and their families turned to bootlegging, digging “dog holes” just wide enough for one man to crawl down on a rope. At the mouth of the mine, the rope was tied to a pulley manned by the miner’s wife and children, who drew up buckets of coal and, at the end of the day, the miner himself.

Hard work and a hard life for all. Nick Bervinchak got it down on paper.

As important as mining life was to Bervinchak, his first love was religious art. In 1958, he responded to a call to submit work to Saint Demetrius Ukrainian Orthodox Church in Carteret, New Jersey. The church needed a new iconostasis. Painters specializing in icons from Europe and throughout the United States applied for the job.

Nicholas Bervinchak was the one who got it, causing an uproar among the other artists. What! A self-taught artist had been chosen for the job! A self-taught artist, yes, and one who was also capable of carving the doors and decorating them in the Byzantine style. The Church of Saint Demetrius had surely made the best choice.

From breaker boy to renowned artist, Nicholas Bervinchak took no short cuts on his road to great art, but as Ron Kramer, a neighbor from Primrose said, “Nick wasn’t in it for the notoriety. He’s one of us.”