Photographer Judith Joy Ross Tells Our Story

Here is my monthly article on artists from the anthracite region. It appears in newspapers throughout northeastern Pennsylvania.

She was born in Hazelton, PA, in 1946. Her dad managed a chain of five-and tens. Her mom gave piano lessons. In high school, she liked to draw. When she won a scholarship to Moore College of Art in Philadelphia in 1964, her parents insisted she study Art Education. Not many artists make a living from their work. They wanted their daughter to have a job.

Today, she, Judith Joy Ross, is “the greatest portrait photographer to have ever worked in the medium,” says American documentary photographer Gregory Halpern, whose portraits reflect the influence of her work. Another American photographer, Robert Adams, considers her portraits a “record of compassion.”

Judith Joy Ross considers herself a “weirdo,” shy and lacking in social graces, yet from the start, she had the confidence and belief in herself that have made her the greatest in the medium she chose 60 years ago.

At Moore she signed up for a photography class and was sent out on an assignment to photograph light. She didn’t know exactly what that meant, but she was drawn to a wet cardboard box abandoned on a cobbled road glistening in the rain. She took a photo. What she saw became an image, and she instinctively understood that the image brought “60,000 times more intensity to reality.”

Her teacher didn’t like the photo. She didn’t care. She was hooked.

Ross went on to get a master’s in photography from the Chicago Institute of Design. She learned a lot from her teachers but followed her own path, which led her back to Pennsylvania. That’s where she has taken most of her photos in a zone circumscribed by Bethlehem to the south and Nanticoke and Hazelton to the north. People are always around me, says the photographer, and with a camera I notice things a lot deeper.

For her portraits, Ross doesn’t use just any camera. Since the 1970’s, she has been using a mahogany and metal view camera set on a tripod. Early on, she realized she didn’t like “stealing.” With a camera like this, one that requires time to set up, and then time for the photographer to position herself behind the lens, her head covered by a black cloth, there’s no chance of going unnoticed. And, to take a photo, she must first establish relationship.

When she’s looking through the lens, Ross sees the world upside down and backwards—and feels connected to the mystery of life. Her goal? To find out something about the person she is photographing and reveal authenticity.

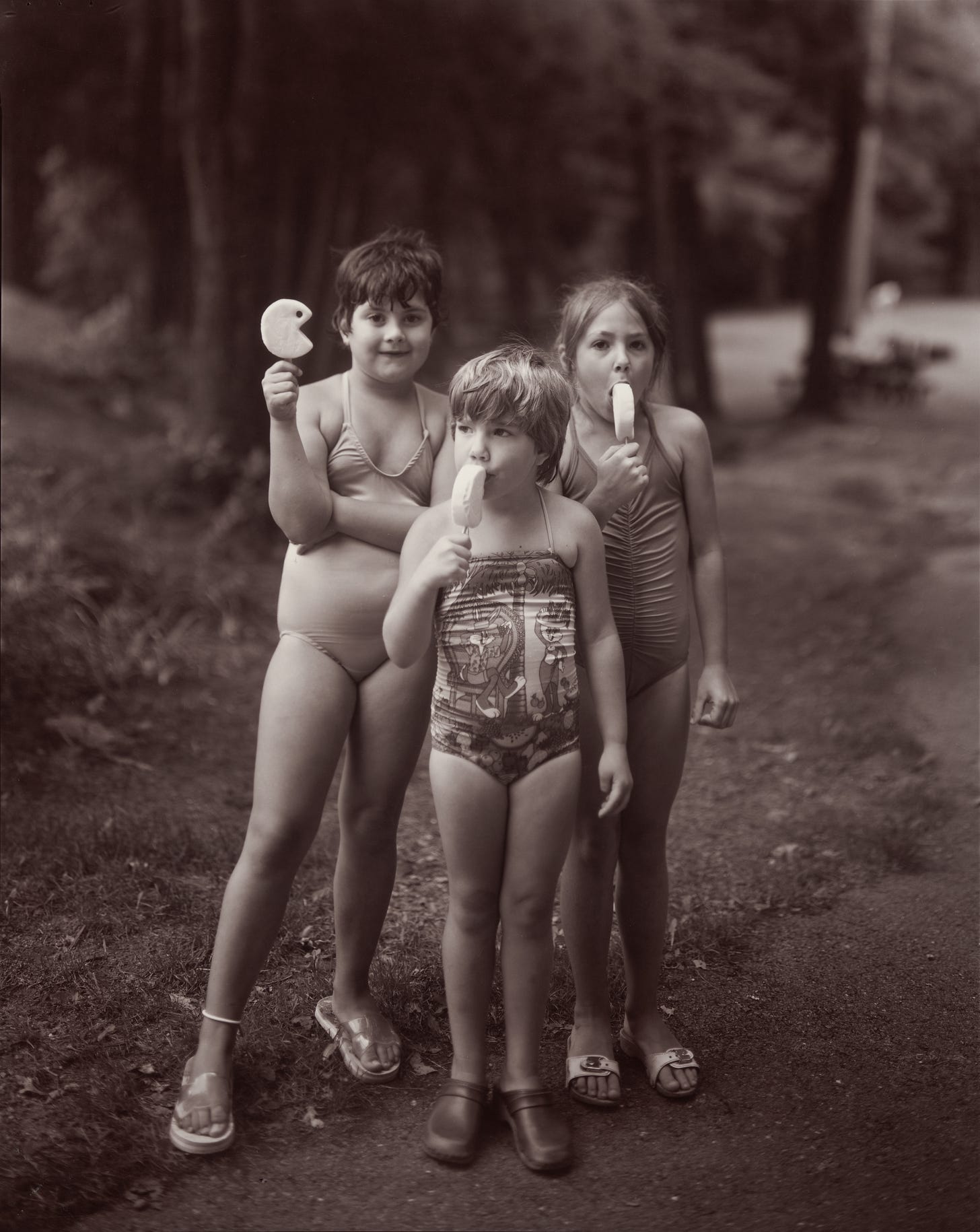

In 1981, Ross’s father died. Looking at other adults, she saw pain reflecting her own. She wanted a place that was safe, where life was good. She headed to Eurana Park, a public pool in Weatherly, PA, where she’d spent happy days as a child.

When she arrived in the summer of 1982 with her equipment on her back, the children gathered around her. She proposed to take their pictures. Once they accepted, her only instruction was “hold still!”

“Eurana Park” was the first series of portraits to earn Ross wide recognition. She went on to do many others.

After the 1982 inauguration of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, she spent two summers photographing visitors to the Wall. This became “Portraits of the Vietnam Memorial.” Ross considers them a “photographic requiem,” where the dignity of those who died and the suffering of those still alive are present in each portrait.

As a follow-up to the Memorial photos, in 1986 and 87, she went to Capitol Hill and made portraits of members of Congress, many whom she considered responsible for the Vietnam War. She took the risk of involvement with men and women whose ideas she did not share. She sensed their power, at times, their charisma, but above all, she sought to reveal them as our flesh-and-blood equals.

When she returned to her hometown in the 1990’s, her mission was to honor the teachers and students of the Hazelton public schools. Setting up in classrooms as discreetly as she could, she took pictures that would make any student or teacher feel proud.

In the 21st century, after 9/11, she took her camera to West Orange, NJ, and made portraits of faces looking east to the Twin Tower ruins. In Bethlehem, she photographed reservists about to leave for the second Iraq war; in Nanticoke, men and women on the job. Or she simply stepped outside her home and photographed people in the streets and shopping malls of Bethlehem, Easton and Allentown.

Judith Joy Ross has exhibited her work in museums and galleries in the US and around the world. She has used her unique photographic talent to reveal truth with love.

Taken together, her portraits tell a story. “Our story,” says Ross, a distinctly American story where the line blurs between “us” and “them,” as we come together in the imperfect but vital experiment of American democracy, worth preserving, worth saving.